INTERVIEW

Candan Kendir (OECD): “Who can know better than people who have first-hand experience with healthcare about how to improve the delivery of health systems for better outcomes and experiences?”

Caroline Berchet (OECD): “There are large inequalities in access to technologies […] Policymakers should ensure that all people can use and access to health technology. Digital health literacy is key”.

Could you imagine being the main character of a theatre play but being ignored by all actors and actresses during the whole performance? That is exactly what happens when the patients’ voices and visions are not included in the policy making processes that have an impact on healthcare delivery.

The Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) knows the importance of considering what patients have to say for improving the design of healthcare policies and policies themselves. Candan Kendir (Health Policy Analyst, OECD) and Caroline Berchet (Health Economist, OECD) see the need of changing the way policies have been elaborated so far and have shared their vision and insights with the eCAN project in that respect.

Question: Latest cancer prevention and care policies include patients’ voices in the policy-making process. Why is this approach taken?

Candan Kendir: Patients and caregivers can provide their experience and knowledge to health policy making and research. In the end, the ultimate goal of healthcare is to provide care to people. And keeping that in mind, who can know better than people who have first-hand experience with healthcare about how to improve the delivery of health systems for better outcomes and experiences?

However, bringing patients’ perspective into policy making is still very rare across countries. For instance, an OECD work published in 2021 to evaluate patients-centredness in healthcare systems found that only 11% of the participating countries included patients’ voices in key policy-making areas.

When did policymakers start to take a people-centred approach for improving the health systems’ quality in Europe?

Candan Kendir: We cannot talk about a milestone event which leads to all these conversations, but we know that years ago this was not even part of the discussion. It was when several international organisations and associations started having patients in their councils or in their advisory bodies that a patients-centredness approach emerged. All that led to now have patients sat in advisory bodies or working groups in Health Ministries.

Are there any national or regional examples that we can consider touchstones to base future work on?

Candan Kendir: There are a few good examples across Europe. However, it is not only about including or engaging patients in policy making, but also about how to do it. We need to agree on when they are needed and which level of implication they will have, because they cannot be everywhere; they have limited resources, time and capacity.

When I think about good examples in Europe there are two countries that come to my mind immediately. One of them is Czech Republic. In 2018, they established a Patients Council consisting of patients’ organisations that works in collaboration with Patient Rights’ Units in the Ministry of Health. Basically, each time there is a new area of work in the Ministry of Health, patient rights’ units think about the kind of involvement patients can have in the issue. These groups gather very regularly, and they also meet with the Ministry of Health once a year, if I’m correct.

What about the second country?

Candan Kendir: Another example is in the Netherlands, at the Netherlands Institute for Health Services Research (NIVEL). They created a council of people with over 11,000 members. NIVEL consults this group regularly for key policy areas that the Ministry of Health is working on, based on the topics and the interest they are forming new subgroups from this council and agree which topics they will address, their role, their involvement during the process…I’m pretty sure there are many examples such as those, in Europe and outside of Europe.

The OECD has launched the Patient-Reported Indicator Surveys (PaRIS) initiative in 2018. These surveys included patients and healthcare providers in the designing process. How is the patients’ attitude towards this new approach of a people-centred health system?

Candan Kendir: We have a very engaged groups of patients and providers in the PaRIS initiative, because the initial proposal came from a bottom-up initiative of a task force, integrated by patient representatives, patient organisations, and primary care provider organisations as well. These people worked together on the study, design and development of the PaRIS Survey. After that, in 2018, we convened a Patients Advisory Panel, with whom we have regular contact. It has been 5 years since we have this patient panel, and I can say that these 10 patient organisations are still engaged. They participated in all steps of the designing and development process, and that was key for their engagement.

“On our end, people-centred approach requires a lot of time and resources. On the patients’ end, because most of times they are not paid for these kinds of activities, they need to use their own budget or resources”.

Which are the main challenges about including the patients’ voice in the policy making process?

Candan Kendir: On our end, people-centred approach requires a lot of time and resources. On the patients’ end, because most of times they are not paid for these kinds of activities, they need to use their own budget or resources. Another challenge is the difficulty of coming to a consensus with all different stakeholders. Sometimes when you work with a group of experts in a survey like this, they would like to add more questions because it is interesting from a research perspective, whereas for patients it might be a burden to answer all those questions. You need to find a common ground to bring all these people together and even if we cannot make everyone happy, we need to make sure that they all understand the reasoning behind the final choice that we were making

Caroline Berchet: An important stake from including the patients voice in the policy making is to make sure the care provides value to patients. From an economic perspective, this allows to reduce wasting in health care expenditure which is critical today given the limited resources that we face. Still today, care fragmentation for people having chronic conditions is too high, having implication on efficiency and health outcomes.

How is it possible to achieve a representative “patient’s voice” that does not leave anyone behind? And how can this measure help to tackle inequalities seen across the European Union?

Caroline Brechet: From a methodological point of view, it is important to make sure that you have representatives from all population groups, so for example by educational level, income level, migration status as well those living in rural or other under-served areas.

Candan Kendir: Yes, it should be upon to all, and it should be also transparent, so no one could think that they did not have the opportunity to contribute. These are two key elements, but on top of that there are hard-to-reach populations that require extra measures. Wales, for example, wanted to ensure that the voices of people from deprived and vulnerable population groups were included in the PaRIS survey, so they decided to go there and talk to people and primary care providers in the region. Being inclusive and transparent are the key things, but sometimes it is necessary to take an extra step. Same thing for people with low health literacy level, for instance.

And outside the PaRIS initiative, which measures does the OECD take to be inclusive and transparent to avoid inequalities when improving the quality of the healthcare systems?

Candan Kendir: When we were preparing the EU Cancer Country Profiles, we had consultations with stakeholders, expert groups and patient organisations. We did not have a formal body of patients that we included in the initiative itself, but we asked European Member States whether they communicate with national patient organisations for cancer prevention and care. Of course, today there are many European projects with Work Packages led by patient organisations themselves. I think this is also another good example, not only involving patients in the projects that we are doing but also partnering with patients’ organisations who can advise us in certain aspects.

Caroline Berchet: At the OECD the question of inequalities is actively addressed. For example, several recent flagship reports present socio-economic inequalities in health status, in access to care or in risks factors to health. Monitoring inequalities is the starting point to shed light on how different population groups are doing, to monitor trends in health inequalities and deploy targeted responses.

One of the documents that shows inequalities across countries are the EU Cancer Country Profiles. What are the report’s highlights on this regard?

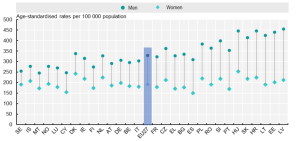

Caroline Berchet: In terms of key findings, I would say that cancer inequalities are large across Europe, but also within countries. Policy actions should target groups on lower socio-economic groups, and among men population. We saw for example that the cancer mortality rates are on average 75% higher among men than women across the EU, that is a large disparity.

The second type of inequality within countries that we can observe is related to educational level. In almost all EU countries, cancer mortality rates among low education groups are higher than those in higher education groups. At the same time, cancer mortality rates among higher education groups are rather similar across countries, but there is a lot of heterogeneity in cancer mortality among the lowest education groups. Focusing on low socio-economic groups will help to reduce overall inequalities in cancer mortality across countries.

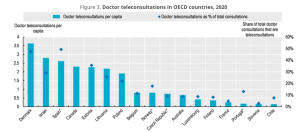

What would you say that are the main inequalities across the EU in terms of digital health?

Caroline Berchet: There are large inequalities in access to technologies, although technologies are key to provide access to care and reduce disparities. One important thing to mention here is that policymakers should ensure that all people can use and access to health technology. Digital health literacy is key.

“The eCAN project will provide some good information on EU practice and evaluate some pilot project’s outcomes that will be useful for sharing experiences across countries”.

The OECD got the status of observer at the eCAN project. How can eCAN and the OECD collaborate in the short and long term?

Caroline Berchet: In the short term, the collaboration with eCAN is a great opportunity for nurturing the work the OECD and the European Commission are doing. The eCAN project will provide some good information on EU practice and evaluate some pilot project’s outcomes that will be useful for sharing experiences across countries. In the longer term, one way of collaborating is to work on the series of Country Cancer Profiles that are produced for each EU member States, plus Norway and Iceland.

Candan Kendir: We know that you’ll implement pilot projects regarding cancer care in telemedicine and you will do an evaluation of it. Patient-Reported Outcomes and Experiences are one of the most important aspects to consider in this evaluation. The experience that we have developed at the OECD over the past years on measurement and reporting analysis will be also valuable for eCAN. On the other side, it is interesting to get the results of this evaluation and see the differences and interpretations that we can make when looking at different works.

The views expressed and arguments employed herein are solely those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the OECD or its member countries. The Organisation cannot be held responsible for possible violations of copyright resulting from the posting of any written material on this website.

Co-funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or HaDEA. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

Co-funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or HaDEA. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

![]() Co-funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or HaDEA. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

Co-funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or HaDEA. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

OECD

OECD